- Second Act Creator

- Posts

- The Gen X Guide to VO2 Max: Part 2

The Gen X Guide to VO2 Max: Part 2

How to train for a higher VO2 max and why building this foundation in your 50s is the secret to thriving in your 80s.

Welcome to the 34th edition of the Second Act Creator newsletter—outlining the Gen X blueprint to flourish in midlife.

Not yet a subscriber? Welcome! Subscribe free.

Good morning,

If you’re a new reader this week, welcome! I’m so glad you’re here.

This is a rare “part two” letter. While not entirely critical, you may benefit from reading last week’s “part one”, which you can find here.

Let’s jump right in! 🦘

1️⃣ ONE BIG THING

The Gen X guide to VO2 max: part 2.

In last week’s letter, I discussed how VO2 max is the strongest statistical predictor of how long you will live. A low VO2 max (lowest 25%), compared to a very high VO2 max (top 2.5%), increases your risk of dying from any cause by 5x. This was documented in a 25-year study of over 122,000 people and confirmed in a subsequent study with over 750,000 people.

That 5x increase in what is referred to as the "hazard ratio" is 3-4 times greater than the risk posed by things like smoking, hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and kidney disease.

But I didn't answer a key question: Why does VO2 max matter so much?

The short answer is that a high VO2 max results from a lot of work over a long period. As Dr. Peter Attia often says, “You can’t cram for the test. [If you] take a person with a low VO2 max and you send them to the gym for a month—they're not going to show up with a high VO2 max on the test.”

A high VO2 max is the cumulative result of consistent and specific training over a long period. In my opinion (and this is not validated in the research), if you can maintain a consistent training routine over many years, you probably are also doing a variety of other healthy things right.

Is it too late to start?

What if your training routine is, well, nonexistent? Or, if you’re like me, it’s sometimes good and sometimes… less than good (I struggle mostly with consistency).

If VO2 max reflects cumulative work over time, is it pointless to start now?

In fact, the opposite is true.

For two reasons:

The most significant health gains documented in the research studies were for people whose VO2 max went from the bottom 25% of the population to the next highest quartile. This alone creates a 2x reduction in your risk of dying, which is larger than the impact of any of the other big health moves you can make (e.g., stopping smoking, treating high blood pressure, etc.).

As the Chinese proverb says, "The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago. The second best time is now."

I’ll return to this to close things out today, but midlife is the perfect moment to build the health foundations you will use in your 70s and 80s.

As a comparison, if you are 50 and haven't saved a dime for retirement, you would certainly be better off starting to invest today rather than waiting until you are 60.

So, today, I will describe how to invest in your VO2 max.

But first, let’s return to my pump and sponges analogy from last week.

As a refresher, VO2 max measures the overall efficiency of your heart's oxygen delivery system (the pump) and your muscles' oxygen usage system (the sponges) when working as hard as possible.

Let’s take a moment to better understand the sponges in this analogy.

How your body makes energy.

I sense that most people think of VO2 max as a number tied to the efficiency of their lungs and heart. Most of us learned that "getting fit" means whipping your lungs and heart into shape, coupled with stronger muscles.

The big eye-opener for me was realizing the real action is at the cellular level—in your muscle cells, to be specific. In fact, whenever I train now, I primarily think about it as putting my cells (and all their tiny mitochondria) through a workout. 💪

Your body needs energy to move. The universal unit of energy your body uses is called ATP (having flashbacks to 10th-grade biology yet?). Your muscles convert the chemical energy stored within ATP into mechanical energy to move your body. It is an amazing system.

The real miracle is that your muscle cells can use many "fuel" sources to create ATP. It is like we are a car with an engine that can burn gasoline, diesel, propane, natural gas, and cooking oil.

Your muscle cells can use phosphocreatine, glucose/glycogen (carbs), fatty acids (fat), amino acids (protein), and even recycled lactate (a byproduct of using other sources, like a car that could run on its own exhaust) to produce ATP.

When are these different energy systems used?

Based on exercise duration. For example, phosphocreatine is used only for the first 10 seconds of activity. Meanwhile, fat sources of energy are used for longer-duration activities (you have a lot of it stored, and it produces the most ATP and the fewest negative byproducts).

Based on energy intensity. You can only sustain medium levels of effort using fat-for-fuel energy systems. As you transition to more intense activity, your muscle cells will begin using glucose-based energy systems (and others).

A big differentiator with these different energy systems is whether they need oxygen, which brings us back to VO2 max. Here's a final biology refresher for you:

There’s aerobic metabolism (with oxygen). This is your body’s clean-burning, long-haul system. It can use fat, glucose, and more for energy (plus oxygen). You use this system when you're walking uphill, cycling on flat ground, or doing anything that you can sustain for a while without gasping for breath.

Then there’s anaerobic metabolism (without oxygen). This is your sprint system. It's fast and powerful, but it burns through fuel quickly and creates more metabolic waste. Think running sprints, cycling uphill, higher-effort rowing, or anything you know you couldn’t sustain for very long.

OK, Kevin, thanks for the biology flashbacks, but why does this matter?

The big idea here is that your body's ability to use all these energy systems is highly responsive to training (and a lack of training).

When you are "out of shape," your body's flexibility to use the different energy systems is low. For example, for someone who is almost entirely sedentary, or perhaps with pre-diabetes or Type 2 diabetes, research has shown that their muscles cells have a greatly reduced ability to utilize the fat energy system (which, remember, is the most efficient and durable system). They will jump right into the glucose/glycogen energy system with even short, low-intensity movements.

As you get more and more in shape, alternatively, you will be able to utilize the fat-based energy system for higher workloads and longer durations. This happens because training leads to major adaptations to the mitochondria in your cells (your tiny energy factories).

As you get into shape, you actually increase the number and the size of the mitochondria in your muscle cells (more and larger sponges).

Just as critically, you will improve your muscle cell’s ability to switch efficiently between the various energy systems (more porous sponges).

That switching ability—metabolic flexibility—is one of the hidden keys to health. It's a big part of why VO2 max has such a big impact on longevity.

This biology diversion is critical to helping you understand what comes next: How to train to improve your VO2 max.

The key idea is that you need to purposefully train the various energy systems. You need to improve your cell's ability to use fat for energy for longer periods and higher workloads. And you need to train your ability to switch efficiently into and out of the glucose energy systems (and into and out of the aerobic and anaerobic systems).

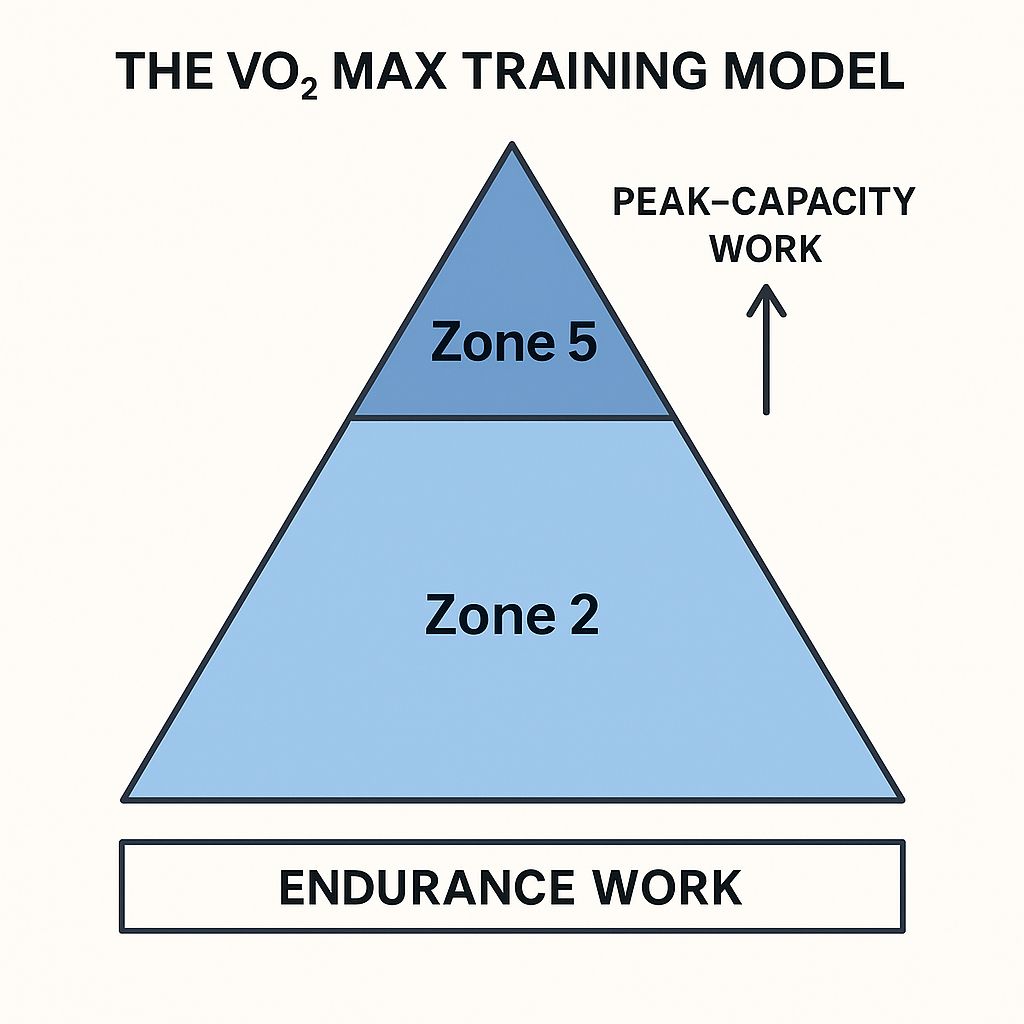

The triangle training model.

To begin with, let's discuss training zones. Many training materials (including Apple Watch and similar products) refer to these zones. What do they mean?

Training zones refer to how hard your body is working during exercise. Different models exist, but the most common uses five zones (Zones 1-5). The zones describe five levels of effort, from super easy to all-out hard.

For example, walking is almost always in Zone 1 for most people, while an all-out burst of effort that can only be sustained for a few minutes would be Zone 5 (for example, running uphill at full speed).

While the Apple Watch and other systems categorize the zones based on your heart rate, the five zones are more accurately understood based on the different energy systems discussed above. Heart rate is an easier-to-measure (but not terribly accurate) proxy metric for the zones.

I'll focus here mostly on Zones 2 and 5 to outline an approach to training to increase your VO2 max.

Zone 2 training is where most of the action is. At the top end of Zone 2 (as you approach Zone 3 in terms of effort), you are pushing the limits of your muscle cell's ability to use fat for energy. As you spend more time training in Zone 2, you will be able to do more work for longer periods while staying in this efficient energy system. This is your endurance work.

Zone 5 is all out. If you are enjoying your workout, you are not yet in Zone 5. It is never fun. But really pushing your limits (and it takes very little time; see below) pushes both your cells and your heart to the max, producing rapid adaptations. This is your peak-capacity work.

With your training, you want to build as large of a triangle as possible. Here's what I mean:

Think of Zone 2 work as building a broad base for your triangle. This base gives you stability and structure for your fitness.

Then, think of Zone 5 work as building the triangle's height.

Some people have a very wide base, with many hours logged in low-intensity training. Others do a lot of interval training focused on short bursts of hard work. Neither group has a triangle with a large surface area.

Many of us in Gen X grew up thinking that the harder you exercise, the better. But most of your gains will come from extended Zone 2 work. Intervals and HIIT workouts bypass the critical fat-based energy system that is the critical base of your triangle.

“Most people overestimate how hard they need to go and underestimate how long they need to go,” Dr. Andy Galpin says.

OK, let's look at a sample training week to maximize your overall fitness gains and increase your VO2 max over time:

Zone 2

3 to 4 sessions per week

Each session: 30 to 60 minutes

Examples: cycling (with no hills), hiking briskly up hills, rowing (if you have good form)

Zone 5

1 to 2 sessions per week

Each session: 3 to 4 intervals of 3–4 minutes hard, 3–4 minutes recovery

Sprints, max effort rowing, hill repeats, bike intervals

You'll notice that you want to accumulate a lot of Zone 2 time each week and tiny doses of Zone 5 work. For example, my current training plan calls for 115-170 minutes a week of Zone 2 and 1-4 minutes a week of Zone 5.

A few critical notes here:

The recommendations above will vary wildly by your current fitness level.

If you are largely sedentary now, you won't be in a position to do the schedule above for quite some time. I would start with five minutes of walking near your house three to four times a week. The goal is a slow, steady, and confident climb where you add just a tiny amount of additional work each week. Yes, getting started is important (and hard!). But a steady and consistent approach is where you will win over time.

If you are already in great shape, the above schedule will not be enough for you.

And finally, as in all things, please do not take any of this as medical advice. Learn your own body, do your own research, and talk to your doctor as needed.

Finally, it is often hard to figure out the amount of effort required to get into the all-important Zone 2. For the majority of people, walking will always be Zone 1 and therefore not sufficient. (But again, I love walking and find it is the single best way for most people to get started. I still walk a lot because I enjoy it so much.)

For the average person our age (Gen X), your Zone 2 heart rate will be in the range of 110-135. But this varies wildly by person and by day for each person (based on things like sleep quality, stress, prior workout fatigue, and more).

A better method is referred to as relative perceived effort (RPE). In short, how hard does it feel like you are working? For Zone 2, you should be able to carry on a conversation while exercising but struggle to do so (lots of breaths between words). Here is Peter Attia talking about and demonstrating what this looks like (ignore the nerdy first minute or so of this and his euro hat, hahaha).

Why midlife is the big moment.

There’s no avoiding it. Getting older sucks.

No aspect of my body has magically started working better than it did ten years ago.

At the same time, I want to be an ass-kicking 70 and 80-year-old.

But here is the thing:

“You don’t get to be a high-performing 80-year-old by being average at 50,” as Attia has said.

You can plan now for the unavoidable decline of aging in two ways:

Slowing the rate of decline.

Starting from a high baseline (not an average one).

This idea motivates me. I am not trying to avoid getting older (I don’t like to place losing bets).

Working on your VO2 max in midlife is the single best investment you can make in your long-term health and, more importantly, your long-term quality of life.

Like your retirement plan, it is not an investment you can afford to make at the last minute.

This (low-fi) graphic tells the story of how work done in your 50s can be the difference between independence and dependence in your later years. The decline over time remains, but the starting level between trained and sedentary makes all the difference.

It can start with a five-minute walk.

It can start by adding more Zone 2 minutes to your week.

It can start by adding Zone 5 workouts to your week (if you already do Zone 2 work).

I could end with a poster-worthy “journey of a thousand miles” quote.

Instead I’ll turn to our friend Mark Twain: “The secret of getting ahead is getting started.”

Thank you for reading my letter each week. It means a lot to me.

I’m going to take next week off for the U.S. 4th of July holiday weekend.

I’ll see you back here again on Sunday, July 13.

Kevin

How did you like today's newsletter? |